Morgan Myers | 07/31/2019

Unfortunately, many of the “great” finds of the viking age were excavated in the 19th century, and by inattentive archaeologists. One such excavation that suffers from poor documentation is the ship-burial found at Gokstad, Sweden. Fortunately, however, unlike the tent finds from the Oseberg burial, the tent’s poles have survived conservation attempts relatively well, but information about them is scant. The tent survives as four supporting poles; the cross beams and pegs have not survived, or—due the the rather remarkable state of preservation the surviving poles are in—were likely buried elsewhere along the ship and never identified.

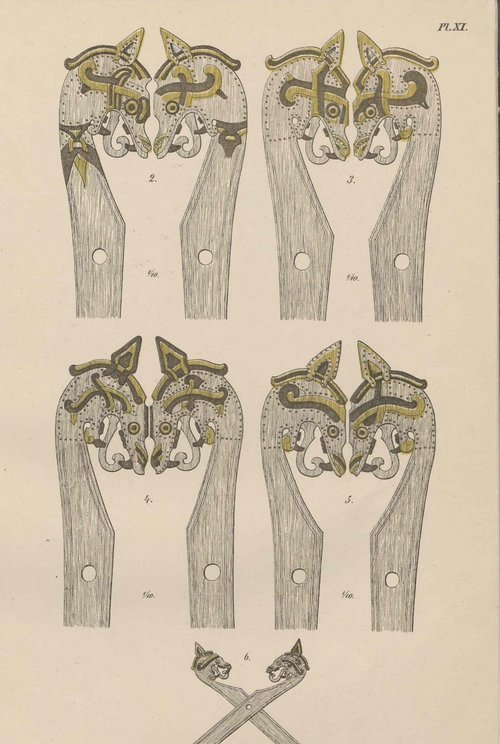

The poles are decorated with stylized beast heads, the sides of each head with a slightly different face (Fig 1.). Based on images I’ve been able to find of the heads (Fig 2-Fig 4), the linework of the face was done with a knife, rather than a v-gouge (irregular widths, depths and angles to the cuts).

Figure 1. Print of the Gokstat tent-poles, indicating the motifs, paint and hypothesized in-facing orientation.

Figure 2. Original tent head, see Figure 1., 5R.

Figure 3. Original tent head, see Figure 1., 4L.

Figure 4. Original tent’s as displayed, note outward facing orientation, as opposed to the Figure 1 orientation. Are the horizontal ovals wear from side-to side stresses or if the heads are inward facing, oval to allow the tent to angle in?

Like the shields that were found along the ship’s edges, the heads were decorated with yellow and black paint. Its impossible to tell from the Nicolaysen’s illustrations if the linework was painted black, left unpainted, or was a color he didn’t record. The paint has not survived conservation efforts, and so far I have found no specific analysis of this find, however, archaeologists at the Danish Nationalmuseet have recently published an article regarding pigments that were used in viking-age Scandinavia.

2021 edit: Soon after I wrote this entry, Vegard Vike of the Kulturhistorisk museum in Oslo wrote a short twitter thread on the Gokstad and Oseberg tents. Information he included was the composition of the paints based on better surviving sections of the Gokstad find, confirming the black was lampblack and the yellow was orpiment. Additionally he provided some detailed images that were not available before, a tool used to create the fluting and linework along the sides (wish I had known about that!), and a possible woolen fragment of Oseberg tent/sail.

For my reconstruction, I compared lampblack and ground charcoal for blacks, and found lampblack preferable due to the inconsistency and large particle size of the charcoal-based paint. Orpiment and yellow ochre were two available pigments in the Viking age, but orpiment would need to be imported, is toxic, and is fairly expensive, whereas ochre could be produced locally (just like the carbon-black), is much safer, and I’d imagine as cheap as the dirt it’s made from. The resulting yellows are fairly similar, so given the above considerations, I opted for ochre. I did several mock-ups of the heads on paper, and decided to contrast the linework using a red paint—and I felt it may also be appropriate, given the use of reds to contrast linework and inscriptions on runestones, as well as saga/edda references to using red as a contrast. For the red, I used ferric oxide (major component of rust): also an available, documented pigment. I combined the pigments with just enough linseed oil (also indicated by the Nationalmuseet article) that the pigment was at a reasonable painting consistency. By weight, the lampblack required substantially more linseed oil than the other pigments to get the “right” consistency.

I was originally going to make a scale version of the Oseberg small tent, but I liked the finial styles of the Gokstad more, and the finial style is more period-flexible through the viking age. I’ve been unable to find what wood the Gokstad tent was made of, however it seems alot of viking-age woodwork was done with material availability in mind, over specificity. The Oseberg small tent was largely ash (much lighter than oak), and I was able to source some fairly wide ash (9”-13” wide) locally. For the cross beams, I found a large oak piece I was able to get three very long 2”x2” poles out of. The Oseberg tent cross beams were apparently differing lengths—so that the uppermost beam was shorter than the ground-running beams—the resulting taper in the tents shape greatly improves the tent’s stability. Hurstwic published a wonderfully documented replica of the Oseberg small tent, and opted to keep the cross beams the same lengths, and use crossing ropes to stabilize things. If you look closely at the holes in the Gokstad poles (Fig. 4), they appear elliptical, which could be due to decay, shrinkage, wear or was intentionally cut elliptically to allow tent to angle inward like the Oseberg small tent. I opted to bore holes at an angle (to give the set-up tent the same angle of the Oseberg find), and further stabilize the tent by using crossed ropes—which has the added bonus of keeping the tent fly from sagging in the center.

No tent textiles have survived, or have been identified, in either burial, though some have speculated the ships sail would have been used to cover the tent, despite the sail being vastly larger than any of the tent finds. Despite the incredible expense of fabric, these likely were separate units due to the incompatible size, and the ends of the tent would be impossible to secure. The Oseberg house tent could feasibly be covered by a sail of 5.6x6.9m; though that doesn’t correlate with the size of the Oseberg ship. For my tent, I was unable to find a reasonable weight woven wool, and decided to go with a thick linen fabric. I’ll discuss the linen’s dyeing, treatment, and sewing in a later blog post.

Figure 5. My own carving, in progress.

Figure 6. Close up of my first painted head.

Figure 7. First time trial setup of the tent, back.

Figure 8. First time trial setup of the tent, front.

Revised 06/07/2021.>

References and resources:

Article discussing the reason for the Oseberg find’s rapid degradation:

- Łucejko, Jeannette Jacqueline, et al. “Protective Effect of Linseed Oil Varnish on Archaeological Wood Treated with Alum.” Microchemical Journal, vol. 139, June 2018, pp. 50–61. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1016/j.microc.2018.02.011.

Link to above hyperlinked document regarding period pigments

- https://natmus.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/natmus/historisk-viden/Viking/Vikingernes_farvepalet/Vikingetidens_farvepalet_Rapport.pdf