Morgan Myers | 08/18/2018

Viking-age bronzes are some of the most iconic works surviving from the era. The excellent preservation of detail—compared to stone and iron—as well as the staggering number of bronze artifacts found, gives wonderful insight into viking-age art; its diversity, beauty and complexity.

I’ve quite a bit of success casting bronze (a copper alloy of ~9:1 Cu:Sn) however, based on compositional analysis of viking age bronzes, most were brasses (Cu:Zn alloys) with tin and/or lead added—making them, in modern terms, gunmetals or leaded gunmetals (sometimes called red brasses). Interestingly, this yields a much a much ruddier alloy than the yellow-gold brought to mind by “bronze,” even when polished.

Since replicas typically are just made of bronze, I had always thought of viking-age bronzes as being a much cheaper substitution for gold (like substituting cubic zirconia or moissanite for diamond), but given the rather stark difference in color between gold/bronze and gunmetals, I think this was, in some cases, an aesthetic decision. Alternatively, since bronze has a melting point of ~1050°C, and leaded gunmetal melts in the ~950°C range, the use of brass and the addition of lead may have been to depress melting point, so that the stoneware crucibles used (which easily deform/break at high temperatures) would survive heating and pouring.

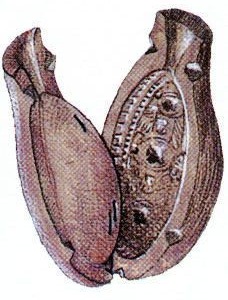

Figure 1. Bronze tortoise brooch uppers. Image: Kulturhistorisk museum, Oslo, Norway.

Figure 2. My brooch upper casting attempts, and a replica Freyja/valkyrie pendant, original in Fig. 4.

In my initial attempt at casting tortoise brooch uppers (originals in Fig. 1), I used a Cu:Zn:Sn:Pb 80:10:5:5 alloy, and cast in a modern, high detail casting investment through the lost wax method. However, due to very poor castings (Fig. 2), I realized the lead I used had a pretty significant iron contaminant, which likely changed the metal’s properties from what I was expecting. In my next attempt, I’ll use confirmed-quality metals, and also attempt a more traditional mold (example in Fig 3.), made of fired clay—which will hold together better than modern investments, and be a better recreation of original methods.

Though my first real experiment with bronze casting was largely a failure, I’ll continue to investigating ways to improve my methods to yield better results.

Figure 3. Illustration of a clay mold for tortoise brooches, based on extant finds. Image: Fugelsang, Signe “Mass Production in the Viking age” From Viking to Crusader . Edited by Else Roesdahl

Figure 4. Freyja/valkyrie pendant. Image: Nationalmuseet Copenhagen, Denmark

Figure 5. Replica of Figure 4. pendant, with severe casting artifacts.

References and resources:

A very informative site regarding viking age bronze casting:

Publications regarding Viking age/medieval bronze compositions in addition to the references found on the above site:

- Bourgarit, David, et al. “Late Medieval Copper Alloying Practices: a View from a Parisian Workshop of the 14th Century AD.” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 39, no. 10, 2012, pp. 3052–3070.

- Garbacz-Klempka, A., et al. “The technology transfer of non-ferrous alloys casting during the middle age”. Metalurgija -Sisak then Zagreb-. 56, 2017, pp. 262-264.